For two years now Paul and I have been living side by side in rooms very close to each other at the flat which we have been lucky enough to occupy in Fentiman Road. Previously we had not known each other; being accommodated in separate residences, he in Battersea, myself in Camberwell. We came to live here by the design of some charitable Catholic women who had sympathy for harbourless young men.

Eventually we two strangers were left by ourselves under the dubious protection of the valley roof above us. It seemed with the departure of the good spirits who first invited us, a malign sort of atmosphere pervaded the place. Apart from the usual weariness of tone characteristic of such old spaces, there was an increase in “bedsit odours” which, along with the growth of dark fungicidal patches on the ceilings, was to prove a great dampener to our wellbeing.

We always had to do most of the house-work ourselves. Paul would spend hours at the ironing board whilst being the prim, design conscious sort that I am, I would briskly flit from room to room with a feather duster, desperately knocking away the sordid grime dulling the potential prettiness of our small collection of butterflies and the stuffed weasel in a glass case Paul said was a family heirloom of his. We had precious little else apart from these things, two record players, a fridge, a T.V. hundreds of books and several thousand records.

But in spite of our efforts to overcome the material squalor of our immediate environment and create a feeling of relaxed homeliness about the place, we were unable to do so. Paul and I had many things in common — such as being white, five feet ten inches tall, weak in the chest and mildly hairy. Yet we were not able to commune successfully. The sad truth is that we didn’t really know each other.

In the mornings I would get up before Paul (because he is lackadaisical) and I would stand behind my door holding a sharp knife at the ready in case he should choose to turn against me. Only after he greeted me with a belated “Good morning” and a courteous grin would I put the knife away and endeavour to open the door communicating the room I occupy with the kitchen, then I would watch him carefully through the gap between the edge of the door and the door frame busily sucking up my breakfast of warm tea and thin porridge through a straw (at the time I could not eat solids due to an illness in my teeth).

For at least a year we continued like this, living separate lives together, connected only by our doors, courtesy and a mutual interest in keeping grasp of a space in which to live whilst about our business in London. The malign increase of fungicidal growth on the ceilings continued; water eventually began to make its way under the tiles, through the rafters and boards into our rooms. We were worried by this — both of us were weak in the chest; it wasn’t long before Paul developed a rasping cough which later turned to bronchitis. I aided him through the worst of this; surprised at my tenacity because I was fortunate enough not to develop any of the symptoms, though at one point I was rather incapacitated with a nasty bout of flatulence.

Then, one day as Paul was musing over the boggish nature of the carpet in the room that we didn’t use much, an ominous swelling appeared in the ceiling above his head. Before I could utter any cry of warning the diseased looking wenn of damp, rotten plaster board, pluked open and a hideous dark projectile, followed by several pints of stinky mud coloured water, flushed violently over and onto Paul’s head. Under the impact of this he collapsed face down onto the floor. Once I recovered from the suddenness of the occasion I could offer him no consolation and proceeded to laugh.

Then I was aware he perhaps did not consider it nearly as funny as me and was probably even a bit angry. Indeed he was angry for some time, because, we discovered the hideous dark projectile which preceded the flush of stinky mud coloured water had been a fair sized clot of semi liquid tar; now horribly besmeared amongst Paul’s hair. That night he suffered the unpleasantness of having to sleep with his head in a bag, for the sake of his bed clothing and his own comfort (we did make an unsuccessful attempt at getting the tar out with paraffin).

The following day Paul went to see a doctor in the hope he might be advised as to how he should rid himself of his new bane but the doctor referred him to a barber who only referred him back to the doctor saying that the cutting of such hair would mess up his scissors, his floor and make business somewhat risky. So the doctor told Paul he would have to allow the tar to “grow out” of his hair. Paul was not happy to resign himself to this — but gradually he did. My flatmate took to wearing large woolly hats to conceal the mess it seemed had become part of his head.

The weeks passed by and eventually the time came when Paul decided he would like to go away for a holiday. It turned out to be a long while before he was to re-appear.

Paul came back one Saturday morning in September; during the twelve weeks that he had been gone I continued to live in London, going about my normal business. The roof over the flat was still leaking and the general condition of things inside carried on into decline, also I found that I was missing Paul’s company.

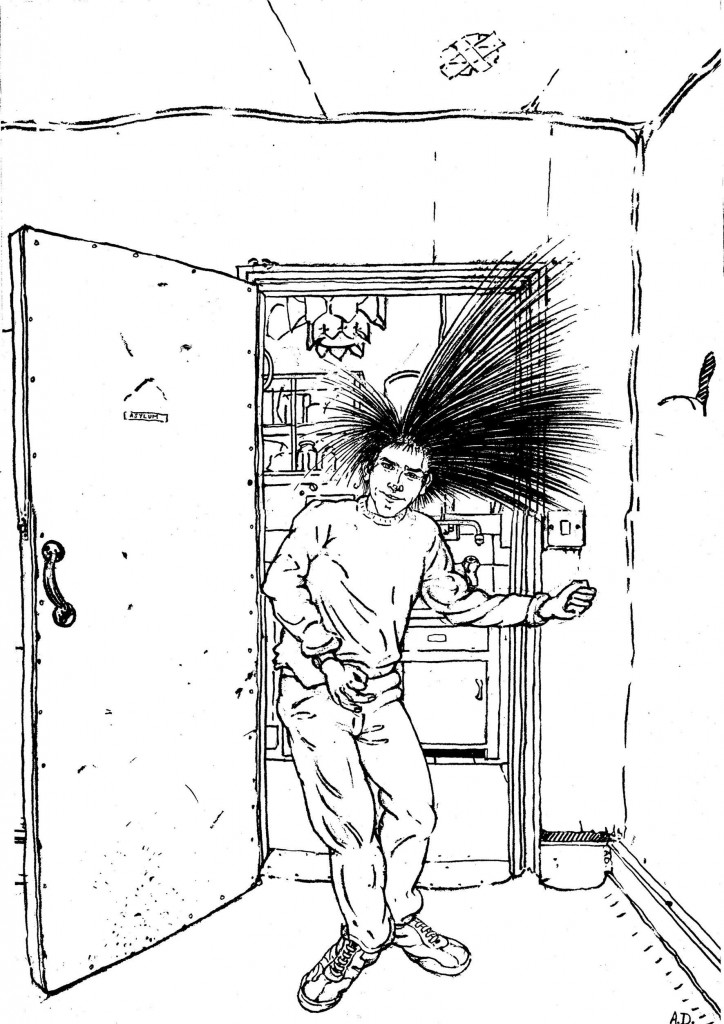

This particular morning I was sitting at my desk trying hard to do some work when the floor boards outside the room made a familiar creaking noise, suggesting someone was standing on them, I wondered who it could be. Not Cyril, the ageing landlord — he was out. An intruder perhaps? For a moment I was afraid and considered preparing for the worst, so quickly took hold of my knife, but then …………. the door opened and in stepped Paul! I supposed it was him, for it looked like a real weirdo had come into our flat. His hair was everywhere. It was really long. It was mad, a voice from under the hair said:-

“Hello Alan.”

then I knew it was Paul, yet the hair still looked mad, so I said to him:-

“Your hair looks really mad.” to which he replied:-

“Yeah, really mad.” then I knew he was “O.K.” and after that we lived happily ever after.

OUR LIFE IN A FLAT by Alan Dedman. Based on a real life story. Approximately 1200 words, first published in Lambeth Arts Magazine.

Scroll down past the social media buttons if you wish to contact Alan Dedman via the comments form on this blog.

Leave a Reply